The Spomeniks of the ex-Yugoslavia

This post was contributed by Siobhan McMahon. She and her husband are full-time travellers currently discovering the Balkans. Siobhan is a professional writer so if you’re looking for a freelancer to write for you, she’s the one (write me at [email protected]. I’ll pass on your message).

PS. I love this post. Don’t miss all the photos of various spomeniks at the bottom.

————————————

It’s early on a Wednesday afternoon in late October 2022. My husband is steering our little hire car along a narrow, winding road that is taking us higher and higher up a heavily wooded mountain about 80 kilometres south-west of Zagreb, the capital of Croatia.

The fog has finally lifted, revealing a blaze of autumn foliage. As we negotiate the bends, sighing trees drop red, yellow and orange leaves in our path. They are like nature’s confetti; a kind of congratulations for making it this far on our quest.

A few minutes later, a simple sign announces we have reached our destination: the village of Podgarić. It is even smaller than we’d imagined, with fewer than 20 homes. They are outnumbered by fat, slow-blinking sheep, which graze lazily beside the main road.

While it’s very beautiful, this idyllic setting is not why we have come to Podgarić. We are here to see an extraordinary quirk of Balkans history – and probably the last thing you’d expect to find in this remote Croatian village.

We are hunting spomenik, a particular and very unusual kind of war monument that proliferated across Yugoslavia’s member republics – Croatia, Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia – after World War II.

Yugoslavia had a new Communist government, led by Josip Broz Tito. The spomeniks’ purpose was to memorialise losses and victories of war, but also to symbolise Tito’s vision for a new Yugoslavia that was future-looking, optimistic, bold, united and egalitarian.

For this reason, spomeniks had a style all their own. They did not feature military heroes on rearing steeds or victims’ faces frozen in horror. Instead, they took the form of abstract, bizarre and sometimes huge shapes made from concrete or shiny metal.

Between the 1950s and 1990s, thousands of spomeniks sprang up around Yugoslavia, often in oddly remote places. Their exact number is unknown because no-one documented them thoroughly and many have since been destroyed.

However, Donald Niebyl, an American biologist and historian who has been cataloguing those that remain in his Spomenik Database, believes there may have been well over 40,000.

“Such a phenomenal wellspring of memorial construction is distinct and unique compared to other European countries during that time period. As such, it immediately becomes evident the importance [that] the Yugoslav government put upon the creation of a mass landscape-wide memorialisation . . .” Niebyl writes.

But spomeniks are far more than just peculiar, photogenic shapes on a landscape. In the era they were created and to the communities where they became fixtures, the monuments held immense significance. Before the collapse of Yugoslavia in the 1990s, large groups gathered at spomeniks on important military anniversaries, and busloads of school children visited them to learn about history.

Nowadays they are sought out mainly by Yugophiles and curious tourists – like me.

My own interest in spomeniks happened by accident. Earlier this year, my husband and I packed up our lives in Australia to spend 12 months exploring Central and Eastern Europe, where we found ourselves staying for a month in Belgrade, Serbia.

After exhausting the city’s tourist sites, I started researching day trips. That’s when an article popped up about a large spomenik in Kosmaj Mountain Park, 55 kilometres south of Belgrade.

Wait, a what? I had never heard of such a thing. The word alone captured my imagination. In Serbia-Croatian, spomenik means “monument,” but to my foreign ear it sounded futuristic, otherworldly and enthralling.

A visit to Kosmaj jumped to the top of our to-do list, but getting there wasn’t easy. We caught two public buses and trudged four kilometres through Serbian countryside to reach the spomenik, which is perched on a heavily wooded hilltop inside a memorial park.

It was worth every aching muscle. “Monument to the Fallen Soldiers of the Kosmaj Detachment” is made up of five massive, angular concrete fins arranged in a circle and soaring 30 metres skywards. It took my breath away.

And just like that, I was hooked on spomeniks – their history, their shapes, their weirdness, their remoteness. Using Niebyl’s database as a guide, and with my patient husband in tow, I have been visiting as many as possible as we continue travelling through the Balkans.

When we arrived in Croatia a few weeks ago, I ruled out a trip to Podgarić, even though it is home to one of the most iconic spomeniks. The village is not far from Zagreb, but impossible to reach by public transport and too long a walk from the nearest large town.

I was not the only person ever to face this dilemma. On a travel web site, I read a post by an American woman who had been forced to give up her dream of seeing the Podgarić spomenik because she could not find a way to get there from Zagreb. I felt sad for her.

At that moment, I decided: no matter what it took, we were going to Podgarić.

Our solution was to hire a car for a day, and after few hours’ driving, we are finally here. We have pootled in and out of the sleepy village a few times, but we’re yet to glimpse its famous spomenik. I start to wonder if we’re even in the right place.

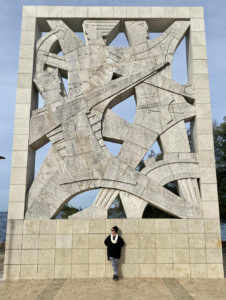

Then we see it! On a bald hill above the village is a giant concrete sculpture. It comprises a pair of asymmetrical, outstretched, brutalist-style wings on top of a rectangular plinth. In the centre of the wings is a convex “eye” fashioned out of metal panels.

I am both delighted and confused by its strangeness. The sculpture looks futuristic, but also as if it could have been created by ancient Aztecs. It reminds me of a pilot-wings badge – except distorted, super-sized and plonked in the middle of nowhere.

But the location of this monument is not as random as it may seem, according to the Spomenik Database. During World War II, the local resistance movement established secret hospitals deep in the woods above Podgarić to treat wounded freedom fighters.

This spomenik was created in their honour, a project spearheaded by local government and regional veteran groups. Croatian-Macedonian sculptor Dušan Džamonja designed the monument, which he meant to represent “wings of victory.” Džamonja revealed his creation in 1967 after two years of construction. In English, its title is “Monument to the Revolution of the People of Moslavina,” a reference to this region of Croatia.

To take a closer look at the spomenik, we turn our car on to a bumpy access road that winds uphill through a paddock. As we draw nearer, I am awe-struck by its hulking size. From wing tip to wing tip, the spomenik is a whopping 20 metres wide, and 10 metres high.

When we reach the top, we discover the sculpture is part of a wider memorial complex. We walk up some steps, beneath a trapezoid-shaped concrete entryway and along a wide path until, at last, I am standing right in front of the spomenik.

Up close, it is even more surreal and imposing. It is also showing signs of age and neglect. The concrete is black in places and there is some graffiti on the metal panels. However, this takes nothing away from its magnificence. I feel tiny and humbled in its shadow.

I have seen photos of President Tito in this very same spot. How lucky am I to be able to experience history so tangibly and intimately?

Now that I am sharing the spomenik’s view, I can see why this location was chosen. The monument looks out over majestic mountain peaks. In the village below, there is a glassy lake that was man-made with the specific purpose of enhancing its vista.

We spend a happy hour taking in the spomenik from every angle until a chill in the air tells us it’s time to leave. As we walk back to our car, I notice a slightly rusted metal plaque set into the path and use my phone to translate its words:

“More than 900 fighters from the whole area of Moslavina are buried here, who sacrificed their lives for the freedom and independence of our people during the national liberation struggle from 1941 to 1945.”

I am stunned; I had no idea the spomenik also marks a large burial ground. We are the only people here today, and apart from the occasional whoosh of a car on the road below, the site is peacefully silent. It seems a fitting place for the soldiers to rest.

As we drive out of Podgarić and begin our journey back to Zagreb, I am already researching which spomenik to visit next and wondering what I might discover there.

A few more spomeniks we’ve visited along with some history

Many thanks to Siobhan for contributing this post!

Related: Castles and Fortresses that you may have never heard of

Related: A hike to the Mila Gojsalić statue, Omiš

Related: Hiking Mt. Kozjak (Split)

im sure ive seen a few similar things in my time, but never had a name to put to them! Now I do although I doubt i’ll remember it in five minutes as my brain is generally a sieve!

I never heard of Spomeniks. Very impressive and weird and I can see why you’re on a quest to discover more of them. And of course the Balkans don’t promote their own monuments. Thank you very much for this article!

Thank you Jack 🙂