Above: Sticker on the hospital sign that says it all.

Above: Sticker on the hospital sign that says it all.

Hate and Sadness in Mostar

We came from Croatia’s pretty Dalmatian Coast, turning inland where the Neretva River runs into the Adriatic. Following the valley of the river, it took another half an hour to get to the border of Bosnia and Herzegovina. It is always interesting entering a new country. You can feel that you are in a different country when entering Bosnia and Herzegovina. Geographically the land changes: the green valley of the river getting narrower. Huge, barren cliffs soar on either side of the river. The valley opened up after 15 minutes and we saw our first village. It isn’t as pretty as Croatia: houses here look as if they haven’t been painted in about 20 years, yards aren’t well kept, cars are older and many look like they are on their last legs. Larger buildings on the outskirts have been abandoned and some are gutted out. We saw our first mosque, the tower interrupting the skyline.

It took another 15 minutes until we entered the outskirts of Mostar. We saw more gutted buildings, mosques, as well as piles of garbage strewn on street corners. The same large, barren cliffs surrounded the valley. “There’s nowhere to hide” said Lissette. It’s true. Anyone trying the climb the hills could be spotted from miles away. It was a threatening and foreboding landscape.

The Center of Mostar was packed with tourists. The Old Town is something out of Ali Babba with its stone-cobbled streets, Ottoman-style buildings, and tourist shops selling Arabic lanterns, copper plates and fez hats. But I’ll leave the touristy side of Mostar for another post. What we really wanted was to understand the history and the volatile mix of culture and religion in Mostar. Because the city is basically a petri dish that encapsulates all that is the Balkans. —— Mostar was the most bombed city in the 1992-1995 Bosnian war, the result of a civil war* between Catholic Croats, Orthodox Serbs, and Muslim Bosniaks. Over 2000 Bosniaks (the principal victims of the war) died in this small city alone. Over 6000 were injured and thousands of others suffered from rape and other forms of physical abuse.

*civil war. I use this term loosely, not everyone agrees with this definition of the war. In 1991 the ex-Yugoslavia broke up as Slovenia and Croatia were the first to claim independence. Bosnia followed in 1992. It immediately resulted in ethnic Serbs and Croats (aided by the Croatian and Serbian governments) fighting for territory. By the end of the war approximately 65,000 Muslims had been murdered (source). It was the bloodiest conflict in Europe since World War II.

Mostar today still shows signs of war, both physically and psychologically. Walk a few blocks from the touristy Old Town and you’ll see bombed out buildings. Walk the empty streets and there is a sense of neglect. There is still a ‘dividing line’ that neither Croats or Muslims cross.

Through our guest house we arranged for a tour. ‘Biba’ (I’ve changed his name to protect him) is 20 years old, a Bosniak (Bosnian Muslim) born a year after the Croat siege of Mostar. He might not have been alive during the war but lives through its aftermath. He’s not a polished tour guide and doesn’t mince any words. “There is so much hate here” says he. “Everyone hates and people are teaching their children to hate”. He said this within the first 2 minutes of our tour.

He walks us up a hill, past a mosque and Muslim cemetery, past a bombed out Orthodox church, to the Serbian Embassy. “They still believe they own it and that one day it will be theirs”. He involuntarily spits on the ground. He points at the hills behind the eastern part of town, a huge promontory that almost hangs over the town. “This is where the Serbs shelled the city”. Pointing at the mountain he indicates that there is a Bosniak town to the left and, not far to the right, a Serbian town. Everything is divided along ethnic lines. I asked him about who fought who in the war. I’m still confused. He explains that at the beginning of the war the Croats and Bosnians formed an alliance to fight the invading Serbs. They repelled the Serbs. Once done the Croats broke the alliance and made a land grab. “They stabbed us in the back”. The siege in Mostar was the ugliest part of the war, turning neighbor against neighbor. Biba’s family lived in West Mostar on the other side of the river. Like many Muslim families they were kicked out of their homes and made to cross the river with whatever was on their backs. Many were shot down as they crossed the river by the same Croat soldiers who had just evicted them from their homes. I asked if he was safe crossing the river with us today. ‘Its ok” says he. But he says that fights break out every day. If you walk in the wrong part of town and someone recognizes you (that recognition often comes from wearing the colours of opposite teams at football matches) there is often the possibility that you might get jumped and beaten. “Things happen all the time” he says.

We walk through the old town, seeing a few tourist highlights (Muslibecovic’s House, the Karodjez-bey Mosque) before arriving at the ruins of Tito’s Mostar Palace. Tito was a Communist strongman, President of the ex-Yugoslavia until 1980. He seems to be more popular now than before the war because, by whatever means, he kept the country united. It’s no coincidence that Yugoslavia erupted into chaos a little over 10 years after his death. Today the palace (he had one in every major city) is a burnt out ruin. “It is used by people to shoot up drugs” says Biba. Drugs among young people are a major problem in a city with no economic base. “The only jobs are in tourism”. We cross a bridge into Western Mostar. The actually dividing line between Muslim and Croats is a few blocks up. As we walk I recognize a building I’ve seen in photos and video. It is a tall, gutted building, the highest on a square surrounded by other gutted, bombed-out buildings. A former bank, this was the building used by snipers to shoot down both combatants and civilians during the war. Today it is another building occupied by vagrants and junkies.

The square was the frontline in the war between Bosniaks and Croats and the main street cutting north-south (Boulevard Dr. Ante Starcevica) is the dividing line between Muslim and Croats. There is a park, ‘Spanish Square’ which commemorates 22 Spanish peacekeepers killed in the war. Biba tells me it is the site of protests against the ineffective government which still consists of Bosniak, Croat and Serb representatives. Corruption is rife. Next to the park is the Gymnasium (possibly the most colourful building in Mostar) which is a high school. Curriculum is divided along ethnic lines, Croats and Muslims take separate courses. Corrected: the school is part of United World Colleges and is the only school where curriculum is not divided along ethnic lines.

The boulevard is one bombed out building after another. A monument commemorating Bosnian War Casualties was unveiled in 2014. It is just a little down the street from the Gymnasium. A few days after it’s unveiling it was vandalized. It lies ruined today. On the same block is a modern hospital. The photo at the top of the page was taken there.

Continuing along brings you to a large Franciscan church. It is at the base of Hum hill, a hill used by Croats to bombard Muslim Mostar during the war. In 2000, Catholics built the 100-foot cross that stands atop the hill, illuminating the skyline of Mostar at night. Muslims find the cross offensive. In 2004, when Stari Most (the Old Bridge, the most venerated Ottoman site in Bosnia and Herzegovina) was finally re-constructed, Catholic Bishops turned their backs on the event marking the inauguration of the new bridge. Religious hate lives on. We met some odd characters on our walk. An old man stopped in his tracks and stared at me as I walked past. I asked Biba about it. “Many people suffer from Posttraumatic stress disorder”. He tells me his mom sometimes yells without realizing that she does. His father had been sent to a concentration camp (where he had lost hearing in one ear). Even 20 years later the after-effects of the war are real. We crossed the boulevard from the Franciscan church and were within minutes among the tourist hordes. “You are the first people who want to see outside tourist area” Biba told us. Every other tour he had given was of the old town.

We walked around on our own later and met an older man and his daughter. They were intent on pointing out an old building. Another shell of a building. It had been a theatre. The lady seemed almost apologetic of the state of her city.

We met some incredible people on this visit of Mostar, people like Biba’s father who welcomed us to his home with a tray of Turkish Coffee. Whether in Croatia or Bosnia, Catholic or Muslim, we have been treated incredibly. Really, truly, I don’t know if we’ve met people on any of our travels that have been more welcoming or friendlier than the ones we’ve met through our first month in the Balkans. That is also why it is so shocking and sad to see the animosity that different groups can have for each other. It is one thing to watch or read about atrocities on the news or in newspapers. Travel there, see it with your own eyes and meet the people and suddenly you have an appreciation. It’s no longer something happening to people that you can’t understand or connect to. That’s the beauty of travel. We’ll come back to Mostar one day. We’d like to see more of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

See this superbly made video on Mostar and the Bosnian War. .

Related: Why Sarajevo is a Microcosm of everything that’s wrong with the Balkans

Related: Random Acts of Kindness when you travel

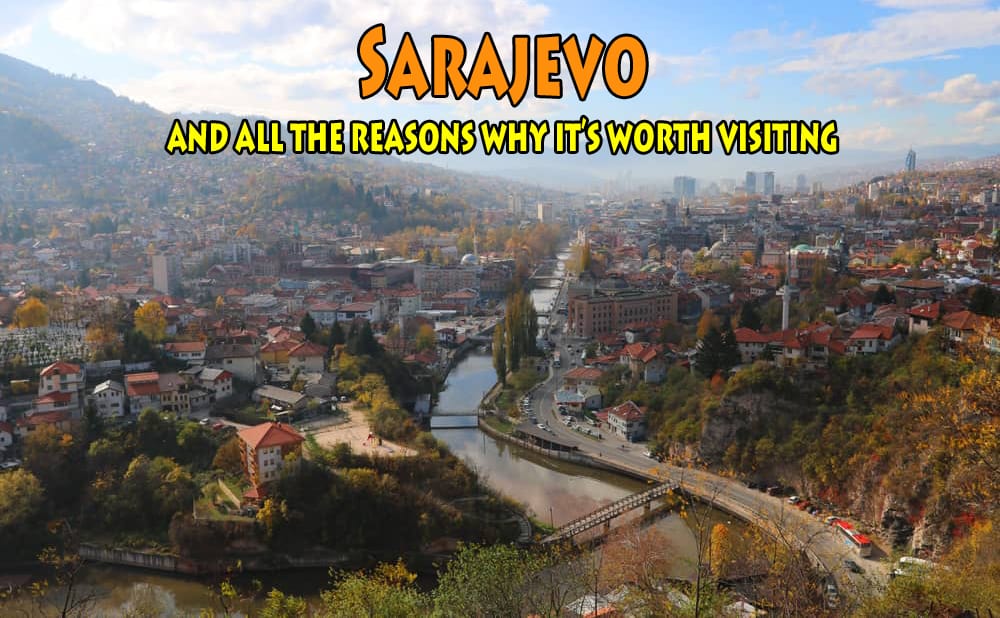

Related: Sarajevo: and all the reasons why it’s worth visiting

Ps. If you find our blog helpful, please consider using our links to book your flights, hotels, tours, and car rentals. Have a look at our Travel Resources page.

The colorful school is a branch of the United World Colleges (UWC). It’s an international boarding high school with students from every single country of the world. Their mission is to “make education a force to unite people, nations and cultures for peace and a sustainable future”. They offer full scholarships for students who get accepted and can’t afford it. It’s quite ironic that someone told you that curriculum is divided (it might be true for local public schools but definitely not this one).

My wife is a UWC graduate and she knows someone in almost every country we visit it’s mind-blowing.

Thanks for the information Rami. You are absolutely right, I looked it up with the information you gave me. Maybe what he told us was the general rule as you say.

Hello! I want to comment on your information regarding the Old Gymnasium. Actually both pieces of information are correct in some way. The UWC occupies only the third floor of the Old Gymnasium. This is an international IB high school that operates separately from the local gymnasium, which is located on the two floors below. Students that attend UWC are from the global community and include all three ethnic constituencies of BiH. The local high school invites students from both Bosniak and Bosnian Croat backgrounds of Mostar. While the school is described as “integrated,” local students follow the two different ethnic-based curricula and do not attend classes together. In essence, it is still very much a segregated school where students are educated according to ethnic identity. This falls under the “two schools under one roof” system.

This contrasts to other schools in Mostar where, since neighborhoods are highly segregated as a result of wartime ethnic cleansing and population shifts, the schools offer the curriculum associated with the ethnic majority present. Students generally attend schools in their neighborhoods, but the option is available to attend a school outside your neighborhood which allows all students access to the curriculum of their choice. These schools, therefore, have a relatively homogeneous student body.

Hope this helps clarify things!

Thank you very much for the clarification as I was getting confused by contradictory information. Very much appreciated!

Inside the building there is UWC and Gymasium Mostar one of the best highschools in ex Yugoslavia and in that school there is separate curiculum that’s actually the only school where Croats and Bosniaks go together and we work together on various projects and interact a lot.

Hi Ilma. Yes, someone else mentioned that below. Thank you for confirming that.

I’m sorry you have heard only one side (Muslim part) of the story, and that you’ve spent more time on the one side of the coast. Mostar isn’t just one coast and Old Bridge, and the truth that ‘Bibe’ speak is questionable. The is a lot of history behind to conclude everything based on few words and sentences. I live in Mostar and I don’t see so much hate with people that live for today, and leave war in the past. I hope you will meet Mostar in brighter shape next time.

Yes, I have to admit his version was a bit depressing and I hope his personal outlook was overly negative. Thanks for injecting a bit of optimism, I hope you speak for most people in Mostar.

Apart from the photo’s, I run across the hatred as well during my travels. After a few times it becomes like heroin, the more you hate the more you want to. It seems to be a sad reflection on our times.

I often think that people need to hate to deflect from real problems or solutions. Some people also have a vested interest in promoting hate, mostly politicians and religious leaders. Look at the Middle East. They couldn’t find peaceful solutions before I was born, they’ll be arguing and fighting over the same petty things after I’m dead. I’m afraid it’s the same in the Balkans. A shame and a waste of time.

Sobering post. We had a similar reactions during our much shorter visit to Mostar. I was moved enough to read several books on the war when I returned. The PBS documentary “I Came to Testify” is another sobering view of the war in Bosnia – you can view it online at PBS or on YouTube. We had similar reactions while touring the area around Karlovac in Croatia. It’s an eye-opener when beautiful scenery and friendly people are interspersed with bombed-out ruins and signs warning of landmines.

Thank you so much for the great comment Paul. I’ll definitely check it out.